Why do we speculate on the love lives of puppets? Because it tells us so much about ourselves.

Why do we speculate on the love lives of puppets? Because it tells us so much about ourselves.

* * *

Most everyone agrees that Bert and Ernie love each other.

The popular puppet pair has made a home in that basement apartment on Sesame Street, hanging a picture of themselves on the wall, sleeping in the same room. Furthermore, Bert and Ernie have a congenial intimacy, sharing food and feelings, talking late into the night, exasperating and comforting each other. They have a commitment, a longevity – after all, they’ve been together for over forty years. They’re a family. But are they family?

How we answer that question tells us very little about Bert and Ernie – but volumes about ourselves.

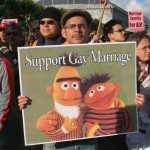

In light of New York state legalizing gay marriage, nearly eight thousand people recently signed a petition urging Sesame Street to “let Bert and Ernie get married“.

When Bert and Ernie were introduced in 1969 – played by Jim Henson and Frank Oz – the characters were presented as friends. This is still Sesame Workshop’s official position. Many consider the duo to be modeled after TV’s The Odd Couple, the famous 1970s roommates who got on each other’s nerves. Back then, on adult television, gay people were mostly invisible. On children’s television, they were unthinkable.

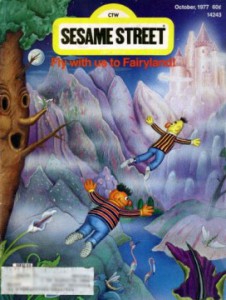

Invisibility was such that this 1977 Sesame Street magazine cover – eminently queer to today’s eyes – could be seen back then without irony or camp. “Fly with us to Fairyland!” Do they mean San Francisco? Also notice this 1980 cover, with Bert and Ernie walking across a rainbow. To contemporary eyes, that picture is gayer than a pride parade.

Invisibility was such that this 1977 Sesame Street magazine cover – eminently queer to today’s eyes – could be seen back then without irony or camp. “Fly with us to Fairyland!” Do they mean San Francisco? Also notice this 1980 cover, with Bert and Ernie walking across a rainbow. To contemporary eyes, that picture is gayer than a pride parade.

Yet, oddly, queer invisibility gave popular culture – as represented in its cultural productions like our puppet pals – more freedom to act queer, more room to be intimate and homosocial without tripping anyone’s homosexual alarm. Oscar and Felix could fight with the passion of lovers, Bert and Ernie could fly away to Fairyland, and no one would point a finger.

Invisibility also forced the creation of gay culture, replete with theater and ritual. Of necessity, we sought each other out, making a community that went beyond coupledom, the proverbial army of ex-lovers that could not fail. In the 1980s, this network proved invaluable when the AIDS crisis hit. “This is our disease and we must take care of each other and ourselves,” Larry Kramer wrote, and the queer community rose to the task, founding advocacy and activist groups, clinics and hotlines, raising money and awareness, gathering and sharing information, taking care of its own.

Mainstream culture finally noticed gays in the early 1990s, and Bert and Ernie quickly came under fire. Reverend Joseph Chambers, a “crackpot preacher” from North Carolina, said in 1994:

Bert and Ernie are two grown men sharing a house and a bedroom. They share clothes, eat and cook together and have blatantly effeminate characteristics…. If this isn’t meant to represent a homosexual union, I can’t imagine what it’s supposed to represent.

Besides being rife with inaccuracies – Bert and Ernie have neither shared clothes nor cooked together – Chambers’ perspective is telling. To the religious right, effeminacy, same-sex intimacy, homosexuality, and probably puppetry are all the same thing. Chambers recognizes the intimacy between Bert and Ernie, but has no way to interpret it other than as a “homosexual union”. He simply “can’t imagine” what else their love could mean. It’s all or nothing. If they love each other, they’ve got to be gay.

Though it comes from a sweeter place, the petition to marry Bert and Ernie shows a similar lack of imagination, creates a similar zero-sum game. If they love each other, they’ve got to be gay, and now they’ve got to be married. You could say that Bert and Ernie find themselves in the same boat as many domestic partners in New York State – suddenly, the relationship must be elevated to the status of marriage or lose all status. As Steven Cheslik-DeMeyer wrote this week,

Don’t tell me the gay rights movement hasn’t become conservative. Now they’re pressuring Ernie and Bert to get married. Because the only legitimate domestic relationship, even for puppets, is marriage.

Now, as elements of gay culture become more visible, Bert and Ernie’s relationship loses much of its complexity – a loss for straight and queer viewers alike. Yet Sesame Workshop’s response to the petition is also problematic, reiterating its position that Ernie and Bert are just “best friends.”

Even though they are identified as male characters and possess many human traits and characteristics…. they remain puppets, and do not have a sexual orientation.

Steve Whitmire, Ernie’s current performer (Eric Jacobson now plays Bert) agrees, “They’re puppets! They don’t exist below the waist!”

However, as a second petition reminds us, this is a clear double standard:

There are Sesame Street Muppets™ who do, in fact, have significant others (Oscar the Grouch has Grundgetta, Forgetful Jones has Clementine, and Count von Count has been linked to several women during his tenure on the show). If Sesame Workshop is truly committed to the idea that puppets do not have a sexual orientation, they should make it a policy across the board. None of the puppets should have romantic relationships on the show.

The elephant in the room, of course, is sex. Really it’s a red herring. This double standard is garden-variety homophobia: gay relationships are about sex, while straight relationships are life as usual. I sometimes get this response when talking about Richard Hunt, whose biography I’m writing, whom I often conveniently shorthand as a “gay Muppeteer”. In many people’s minds, this means I am writing some sort of seamy sexpose, rather than (ideally) portraying the whole person as a role model that everyone, but in our own special way the LGBT community, can be proud to identify with. Though Hunt, at least, existed below the waist.

Personally, I don’t want to think about Ernie leaving anything but cookie crumbs in Bert’s bed. But it is not talking about sex to say that a lot of queers grew up watching Sesame Street, and saw something of themselves in Bert and Ernie and their bond. Perhaps they saw something of the life they wanted to live one day, something they didn’t see on, say, The Brady Bunch. Role models are hard to come by, particularly for the LGBTQ community during the decades of not being seen, not being named. Perhaps there is power in naming Bert and Ernie as a romantic queer pair. (Which, still, is not the same as marrying them off.)

Yet I resist defining Bert and Ernie’s relationship in this way – or in any way, really. To flesh out the characters like this limits their complexity. As my friend James V. Carroll says, “Bert and Ernie, like so many classic muppets, are abstract concepts that are intended to reflect the audience’s experience.” Let’s leave Bert and Ernie open for interpretation. Bert and Ernie spark such easy controversy – as well as easy affinity – because so many of us see ourselves and our loved ones in their relationship. We don’t want to lose this connection, don’t want to be told what to make of the affection between them.

And there have been so many lovely interpretations of Bert and Ernie’s relationship, each with its own “evidence.” They have been seen as kids; sometimes they remind me of my dad and uncle as young boys, whispering into the wee hours in their adjacent twin beds. Michael Davis, a Sesame historian, calls the pair “a projection of the real-life friendship between Jim Henson and Frank Oz,” a fitting tribute. And in Ernest and Bertram, a 2002 mashup with Lillian Helman’s The Children’s Hour, Ernie and Bert become closet cases, with a tragic end.

Ideally, what this sort of speculation comes down to is self-identity. Let’s let the characters speak for themselves. In a 1983 pageant, directed by Ernie, Bert plays the role of Cupid. Ernie tries to give Bert a prepared script on the topic of love, but Bert prefers his own words. His perspective is pretty spot-on, in my opinion:

Love’s a simple thing to see

Why go on for hours?

With oatmeal in a bowl to love

Who needs hearts and flowers?

He winds up the song by declaring his love, as well as his exasperation, for Ernie:

Even though his silly tricks can drive us far apart

I’ll always have a special place for Ernie in my heart.

And really, isn’t that all we need to know?

Cross-posted to The Bilerico Project on August 12, 2011.