Peter Dorosh

Yet Dorosh is a top local birder, having just stepped down after 12 years as president of the Brooklyn Bird Club, and running the Prospect Park bird sightings blog. We sat down in Prospect Park to talk about his story, the accessibility of birding, philosophical differences among the birding community, and, of course, how best to get the birds.

Jessica Max Stein: So here we are in Prospect Park. You work for the park, right? What exactly do you do?

Peter Dorosh: I’m the field technician for natural resources, in the landscape management department. I build habitats.

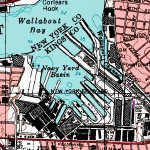

JMS: And you’re a fifth generation Brooklynite? What part of Brooklyn is your neck of the woods?

PD: Yep, fifth generation Brooklynite. I live in Windsor Terrace. I lived for 32 years in the Wallabout Bay area, by the Navy Yards. That’s old-time Brooklyn. You have to remember, Brooklyn is known by its neighborhoods. Wallabout Bay is now generically called Clinton Hill.

JMS: Did you ever feel like you didn’t want to be a birder in the city?

PD: Naah, the city’s the best place to get all the birds in migration. It has to do with the lack of green space, so whatever green space we have here are like islands or oases for these birds to come in and rest, refuel, eat, and all that. There’s no better place than a city park, where you can see all of them in a matter of hours. If you did it all day, especially in spring and fall, you could easily get 100 bird species. I think the most I’ve had with a friend was 117 species. Amazing, isn’t it?

Right now we have a Varied Thrush in the park – first time ever. I saw it this afternoon. A whole bunch of birders came from everywhere to see it, because it’s from the Pacific Northwest. Occasionally birds will get lost, or hit by a storm.

It’s been exploring, because it’s confused, probably. Disoriented. He’s like, “This is not my kind of habitat. I belong in the Northwest.” So he’s trying to figure out where he is. Unfortunately, it’s a survival of the fittest thing. It happens. You know, you get lost. You’re driving in a car, down the road and you take the wrong exit – same thing happens with birds.

JMS: How did you get started with birding?

PD: For me, getting my first bird, I had no connection with birding. I was 14 years old, 1977. My father had just passed away. I looked out my back window. I lived next to the highway – you’re not expecting any birds. Not good habitat. But here’s this bird and my mom says, “Yeah, a scarlet tanager.” Brilliant red tanager. Black wings.

Something triggered me in loving nature after that. I thought, “This is great.” I had no hobbies back then. Being a hearing-impaired person, you don’t have much in the way of leisure or sports or varsity, particularly. It’s difficult for a deaf or hearing-impaired person to be incorporated into society.

So I was really quite impressed and excited to see this species. I persuaded my mother to get me binoculars. Then I started going exploring. I started here, in the park, but I read in the Daily News about Jamaica Bay. The timing was perfect. I said, “I gotta get out there!” So I was about 15 years old, and I got on the A train, and I went out to Jamaica Bay. I figured out how it worked. I’m a young teenager with hearing problems, and I went to Jamaica Bay and explored the wild. This is like nirvana for a birder. It’s a new world!

When I was doing the exploring, I went to the visitors’ center there, and that’s when I saw on the bulletin board, they had a little club: Brooklyn Bird Club trips. A little business card, that’s all it was, and that’s how I got started.

Soon I went on my first walk with the club, to High Tor in Nyack, led by Ron Bourque. Then I got more active. It was hard with college, but after college I got really into it.

I went to Brooklyn College, then transferred into Baruch College, CUNY. I was a geology major at Brooklyn. I found I wasn’t scientifically oriented. I did very well in geology, but the chemistry, the physics – that’s why I went to business school. I graduated with a marketing management degree from Baruch.

And then I got very involved with trips and walks and so on. Made a name for myself. I mean, how many deaf kid birders do you know out there? Not that many.

Prospect Park, aerial view

JMS: How did that 14-year-old kid wind up as the president of the Brooklyn Bird Club?

PD: I met my friend Paul Keim – he’d been president of the club for over ten years. I met him here, in the park. That’s how it’s always been, throughout the club’s 100-year history, people meeting each other in the park.

So I got some really good friends through the club. Then they asked me to become the treasurer, because they needed someone honest, so in 1993 I became the treasurer. I was treasurer for 8 years. I was working in a bank, so I was running the account from my own bank. Then the president stepped down in 2001, and they needed somebody, so they asked me to take that on.

A couple of years later I also took over the newsletter, because the editor left. And eventually the trips, too. It just happened to be that particular time, the cycle – they needed people. But I also had a very creative mind, so that’s why I was doing the newsletter.

In college, I actually flunked English. But what helped get up my confidence and comfort zone was a listserve called e-birds. I would write stories about birds that were seen here that day. I would do it in a poetic way. And that’s when I started getting more comfortable about the grammar, and structure, and paragraphs, and so on. So when the editor left, I was asked to take that on, because there was nobody else at the time. It was hard in the beginning, but then as time went by – because I was writing for about ten, eleven years – it got better.

As editor, but also as president, I kept my eye on conservation, especially in Brooklyn and Queens. I estimate I must have written about 25 letters about conservation issues. For example, Jamaica Bay wanted to build a bike path, and destroy habitat. We fought that. I think it helped.

Another one was the Ridgewood Reservoir, in Queens. They’ve got a former reservoir that the city wanted to turn into ballfields. But since its decommission, it became a natural wonderland, it became habitat. So that was another thing we fought.

Now we’ve got Jamaica Bay that’s an issue: the extension of the runway at JFK, and the pipeline at Floyd Bennett. Those are important things that our administration, our president, should be watching and fighting. So I pride myself on that.

I held on as president for 10, 12 years. But it’s important that the club go through change. I believe in democracy, I believe in term limits. Even though we had no real term limits. We’re a very casual organization. But it works, that way. It’s a loosely affiliated group of people, but everyone’s united, because they love the club.

JMS: What would you say your legacy is as president?

PD: My legacy with the club first would be the centennial. That was most important to me. The society first started in June 1909 when two guys named Ed met on Nellie’s Lawn – right here in Prospect Park – became friends, and their wives, too, and so on, and they all got together. It was only six, seven people, and they said, “Why don’t we form a bird club?”

So in 2009, I felt that the club should have a big celebration. I planned trips to celebrate the centennial, exploring all of Brooklyn: the Botanic Gardens, Marine Park, Canarsie, Coney Island. I also got an old-time leader, someone prominent, to lead a trip once a month. And I did a lot of Prospect Park walks, because that’s where we were founded. So that was fun, that was a great spin on it. And in the newsletter, I wrote about the history, how it first started.

We had a big party for the centennial on June 19th, 2009, with around 100 people. It was great. I had wanted to get former club president and bird artist John Yrizarry to speak, but at the last minute he couldn’t make it. But we had somebody just show up, and it turned out he was the president of the club when they celebrated the 50th anniversary! His name is Max Wheat. He was the former poet laureate for Nassau County. He spoke, and what a speech he gave. I was exhilarated by his speech. I said, “Somebody was looking over the bird club.”

The second legacy is bringing the club into the digital age. Before the centennial, we had our newsletter printed on paper. But the cost was getting too high for our small membership. I told Janet Zinn, my webmaster and newsletter creator, “We should wait until the end of the year. Then, when the new centennial begins, we’ll go digital.” You can also see our newsletter on the website.

JMS: How did you get started doing your birding blog?

PD: The blog came about because there used to be a report called the New York City bird report, run by a guy in Manhattan. But eventually he quit it, because he had family obligations. So people kept asking me, “What’s going on in the park? What have you seen lately?” I said, I’m going to go crazy, with people asking me in emails. So I said, Why not create a central information station, so that people are empowered to look it up themselves.

Essentially the blog is a news board. A bulletin board. I also post other information, events. A lot of people have come up to me and said they’re so glad about the blog. We had like 300 hits in one day with the varied thrush. I don’t have to do it, but I do it out of my heart. I know people out there want to know.

And it’s a good way to promote birding. Then if people take an interest in birding, they might take an interest in conservation. You’re opening a whole new world for people. So that’s the beauty of it, you’re introducing people to a new leisure, and then they go on and take it from there. It’s like you’re sending out disciples, and protégés, and hopefully they will pass it on. That’s what makes people so humane and good to other people. We’re on one planet, share it.

JMS: I noticed that with the thrush. People sharing their binoculars…

PD: Yeah, exactly. People telling you where it is.

JMS: So you talked before the interview about going out birding with a friend of yours who’s an ear birder. How do you like that?

PD: Well, it doesn’t matter to me if he hears something, because I can’t hear them at all. I have profound loss. I can’t hear them. Maybe a cardinal I might hear, or a Carolina Wren, they’re very loud. But the higher pitches than that, I can’t hear.

JMS: Do you find that you compensate for not hearing the birds – do you maybe see better, or notice more?

PD: Oh yeah. I see them better. I’ve been doing it for a long time, so I know, or I have a good thinking process, as to what particular species that might belong to. I might see a bird for the very first time, but I would know what family it belongs to. So I have an idea. Then I’ll go to the field guide and look it up, because I can go right to the family, and say, “Oh, that’s the bird!”

Black-Throated Green Warbler

My friend Paul is a very good ear birder because he’s a musician. He’d be, “Oh, we have a black-throated green over there,” or another warbler. We’d go, “Where, where?” He would point, “Right in that area, right there,” and that’s when I would see the little movement, and I’d be on it.

JMS: In a way, you’re the opposite. You have the special talent in the other way.

PD: I’m a eye birder, right. As long as I’m not talking to somebody. Because I’m a lip-reader, so my eyes are looking over here instead of there. But when I’m out on my own, yeah.

You also have to be very patient. You get your gut feeling, you might see the tiny movement, but you have to be patient and wait for it to come out. And also it’s important to have optics. Good optics. These binoculars are not expensive, but they’ve got a wide-field view. That helps. It’s a skill in using the binoculars too. But most of the time, if you’re looking, you wait for that little movement, and that’s when you know. Patience is a virtue, and it’s the most important skill to have. And it’s practice. You have to keep doing it. You can’t just sit and put the binoculars away for three months.

I’ve done it so much. I love to be outdoors. I’m a big birder, but now I’m more of an outdoors person too. I chase butterflies on occasion, I like the flowers. I love discovering birds in new habitats, in new places. That’s the fun part. Being out there, enjoying the great outdoors.

But that’s how I’ve gotten so good with the eye birding. It takes two things: you’ve got to have not only the ability but the motivation or willpower. It’s a common bird, so what? It’s great to see that bird anyway. You can’t be dismissive, “Oh, it’s just a common yellowthroat.” They’re pretty birds! They’re bright, they’re yellow. Okay, maybe one of these days, you get a cerulean warbler. But that’s the reward that benefits the time you put in. That’s the most important thing: being out there, and enjoying what you do.

JMS: Has it ever been challenging to be a hearing-impaired birder?

PD: Anybody, with any physical disability, can go out and enjoy birds. Not just hearing-impaired, but physically impaired. I’ve seen people in wheelchairs go out birding. Though I sympathize with them, because a lot of areas they can’t access. If you go to Jamaica Bay – and I brought this up with an administrator over there – their paths are gravel, so a person in a wheelchair can’t access them.

I’ve not yet met a blind person birding, but I’ve heard a story where a person who was blind was also one of the most incredible ear birders around. A beautiful story. This group was being led by a blind person, who was calling out the birds to them, and telling them exactly where the bird was. Isn’t that beautiful? So that gave that person a purpose, something beautiful, something that made him an important part of the world.

Everybody counts. Everybody’s precious. So I don’t think it has anything to do with the disability, but the person themselves, the person within. The human spirit, that’s the most important thing. Over disabilities. Someone could be an amputee, but somebody would help him hold binoculars to his eyes, or he might have prosthetics, but he’d still have that drive and that desire to not let something like that defeat him, but to get out and enjoy life. The quality of life. That’s it.

JMS: That’s funny, somebody said that phrase to me the other day, quality of life. Seems to be the theme of my week.

PD: Quality of life. We need to make it an important part, to include everybody. Whether they’re beginners or with a disability or whatever, if they want to be a part of it, bring them in. The trend nowadays, in the last 20 or 30 years, has been competition. Egos, ego birding. I find that a terrible tragedy.

But it’s true of any discipline or leisure. You’re going to have joggers that try to be the fastest, you’re going to have that small minority that’s gung-ho or egocentric. But the rest of us, we don’t have to hang out with those folks. I don’t.

JMS: I think there’s different kinds of birders. Some birders want to just glance at it, check it off, get the numbers.

Gyrfalcon

PD: Tickers. Listers. When I was younger, I used to chase. I still chase, but in a more mellow way, more casual. We just chased a gyrfalcon out in Jones Beach. That was the top bird I wanted to get in my life. A gyrfalcon is a dream bird. It doesn’t come down here. It comes from the far north, the tundra. They don’t come down, and they’re rare, so to get one just tops the list.

25 years ago, I was with two friends in Breezy Point – which has been devastated by Hurricane Sandy – and I was lagging behind them, I was carrying the scopes. So I was tired, and my friend Paul turned around real quick and waved his hat. I was saying to myself, “What is he getting all excited about?” He came running toward me, and he said, “We just got a gyrfalcon.” It flew right in front of him. You should have seen my face just drop. I didn’t see it.

So last week, the gyrfalcon had been reported at Jones Beach. I drove down there – my first attempt at a gyrfalcon, really. We waited an hour and a half, I was waiting in the car, it was windy, all these birders were waiting. I spotted it going in the marsh. I could see it: it landed on an osprey platform nest. A friend told me, “Go to the highway.” We got the bird in the scope. Whoa. Massive bird. One of the largest falcons in the world, and I got it! Took me 25 years. So, I was happy.

I went so many years looking for this bird, and I got it on the first attempt. So you see, there’s a lot of stories, but there’s a lot of irony.

My girlfriend and I went for the Northern Hawk Owl in New Hampshire about four years ago. The irony there was when we were looking for the owl, we couldn’t find it. We took a break. We were eating in a waterfront restaurant, looked out the window and there’s the bird. Right where we’re having lunch! The bird was perched in the pine tree on somebody’s shorefront property.

Same with the Varied Thrush. The birder that came up to me didn’t know me, but he said, “I got a Varied Thrush,” and I was a little skeptical, because we never had one in Prospect Park. But he said, “I live in Washington State, I’ve seen these birds,” and that’s when I realized it was a reliable report.

So you have stories, that you think of years later. It’s not just the bird – it’s also the beauty and the irony and the story and the people. The human angle, that perspective. I mean, anybody can check off a bird.

Great story! Thanks JM.