Cape Cod in February has an austere beauty: sand dunes draped in snow, grey-streaked skies, a generous silence. My friend Mallory and I parked outside the house five minutes before our noon appointment and stood by the car getting our bearings. The front door seemed unused, with no path broken to it through the ice-crusted snow, yet a wall of trees blocked the driveway from the back of the house.

“Back here.” From behind the trees came an instantly familiar voice. I had known that voice, in its infinite variations, since childhood, from countless hours of watching the Muppets: the joyous enumerations of Sesame Street’s Count von Count’s (“The Count”); the easygoing, raspy laugh of The Muppet Show’s Floyd Pepper; the reedy, confiding tones of Fraggle Rock’s Gobo Fraggle (to name but three). It makes me smile, now, that I heard Jerry Nelson’s voice before I saw his face, for I had known his voice so many years.

“Do I hear a twang in your voice?” Jerry asked Mallory, once we were settled in the kitchen.

“I’m from Kansas,” she said proudly.

“I’m from Oklahoma,” Jerry said. “I like to say, I’m from Oklahoma – far from Oklahoma.”

~

When you are truly good at what you do, your work looks effortless. For a television puppeteer, double this: invisibility is intrinsic to the performance. The irony of Jerry Nelson’s half-century career with the Muppets, this studied anonymity made him an unrecognized, ubiquitous icon.

A master of the craft, Nelson brought to life an innumerable, nuanced and wildly divergent cast of characters, from tiny frogs to full-body monsters. His unparalled vocal versatility led many to call him “the man of a thousand voices.” Joked a colleague, “Every time I didn’t recognize a voice, I’d go, ‘Well, must be Jerry.’”

One of the earliest performers to join Jim Henson in his then-fledgling Muppets, Nelson had an almost Forrest Gump-like ability to find the action, moving amidst countless countercultures, from beatnik to hippie to Muppet to punk. He made himself welcome wherever he went, entertaining everyone yet blending in seamlessly, just as in his work.

By the time I met him, Nelson had brought together work and play, approaching most pursuits with the same serious irreverence. He had integrity in the truest sense, consistent with himself, grounded, grateful. A veritable Zen master at enjoying the moment, Nelson was great company. If such a judgment can be made: this was a life well lived.

Early Days

Jerry Nelson was born on July 10, 1934 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “I only realized recently that my whole life was in preparation to do the kind of job I had with the Muppets,” he said. “Of course, I didn’t know it when I was ten years old driving my mother crazy, making funny noises, discovering and stretching my imagination, playing with my voice.”

The family often listened to the radio together. “That was probably where I became interested in the fact that you could regulate your voice and do different characters,” Nelson said.

Nelson married Jacquie Gordon in 1960; their daughter Christine was born on August 14th, 1961. “When Christine was born, Jerry and I were living the precarious, ever-hopeful lives of out-of-work actors in New York,” writes Gordon in her memoir Give Me One Wish. “Jerry’s hero was Jack Kerouac, and my hero was Jerry, and we saw ourselves as part of the beat generation… We lived in a four-room $85-a-month walk up on East 89th Street.”

Nelson first crossed paths with Jim Henson in 1956 while working as a page at NBC affiliate WOR in Washington, DC. “I had just returned from military service,” he said. “He and Jane [Henson] were rehearsing for that evening’s show of ‘Sam and Friends.’” Yet he entered the field of puppetry not through Henson, but through Henson’s predecessor and mentor Bil Baird, whom Henson credited as having “taught him most of what he knew.”

Nelson was routinely humble about his 1963 audition for Baird. “Usually when people ask me how I got started in puppets, I say, ‘‘I lied, and I wore cowboy boots,’” Nelson said. He bluffed about his puppetry experience, gambling – correctly – that he would learn on the job. And he drew on Oklahoma to his advantage, later musing, “I think that [the boots] helped a lot, because Bil was from the west.”

Richard Hunt “right-hands” for Jim Henson as Ernie. Frank Oz plays Bert. Sesame Street set, late ’70s/early ’80s.

Nelson joined the Muppets when Frank Oz was drafted in 1965, creating Henson’s need for a new puppeteering partner. Nelson often jokingly recounted a moment of panic when Oz came into the office on the day of his induction: the army hadn’t taken him. But Oz took a six-month sabbatical to Europe, and Nelson stayed on the job. He paired with Henson, “right-handing” (assisting) as Rowlf the Dog on The Jimmy Dean Show and touring cross-country with Dean in summer 1966.

Yet this promising start fizzled out. “Frank came back in ’66, and up till ’66 we did a lot of work, and then it kinda tailed off,” said Nelson. “Jim said, ‘Well, I don’t have enough work for all of us, and you’re the last one to have joined, so I’m going to have to let you go.’ So I went back to work for Bil Baird.” That same year, Nelson’s daughter Christine was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. He worked intermittently with Henson on both traditional Muppet vehicles and more experimental material, including a hypno-calm cameo as a monk in 1969’s The Cube.

“A strange time in my life,” Nelson said of the late ‘60s. The famous Summer of Love found him in San Francisco, enjoying bands such as Jefferson Airplane. “I’ve dug them from in front,” he wrote. He spent most of 1969 in L.A., where he saw Emmylou Harris play at The Farm. “She sat on the roof of the house and sang with John Sebastian, who was at the time living in a Teepee on ‘chicken flats’ up behind the main house. The same place tie-dye Annie, who started that fashion episode lived.”

Though California provided plenty of adventure for the young performer, Nelson didn’t feel drawn to extend his west coast stint. “I couldn’t do anything out there, and I still wasn’t a puppeteer in my mind, I was an actor,” he said. “Nothing much happened out there, and my daughter became very ill, so I went back to New York to be with her.”

Nelson was “floored” upon returning east in 1970 to see Henson’s latest collaborative endeavor – just finishing its pilot year – a children’s show that creatively combined education and entertainment, teaching kids while keeping them riveted. “When I saw it was the Muppets, I went, Wow,” Nelson said. “So I called Jim and told him I’d like to come over and say hello.”

Nelson made a prescient move. Sesame Street would go on to revolutionize children’s television, becoming a veritable institution of the field. In its near half-century life span (and counting), the show has aired in 120 countries, in twenty different international versions, and won over a hundred Emmy Awards – more than any other show in history.

But in its early years, at least, a group of artists was just trying to make each other laugh.

Sesame Street’s ‘Salad Days’

Many describe the early years of Sesame Street as the “salad days” of the show. Performers were welcome to suggest ideas, fine-tune their lines, push the humor ever further. Nelson thrived in this creative, collaborative environment.

Overall, the troupe knew that if they enjoyed themselves, so would the audience. “That’s the thing, as much as anything, we were trying to do when we worked puppets,” Nelson said. “We were trying to make each other laugh, or make Jim laugh. Or [Sesame director] Jon Stone laugh. Because we knew if we got them, it was funny.”

Nelson and fellow performer Richard Hunt had such a fun dynamic that characters such as the Two-Headed Monster sprang from their improvisations. “We were goofing on the set, and there happened to be a couple of writers in the studio… and it became a character,” Nelson said. “Usually we would talk over a bit before we did it, outline it, and then we’d just play with it.” This sense of play shines through the Sesame behind the scenes clip below. Notice also that Nelson, as the left side of the monster, is puppeteering left-handed.

Nelson’s most well-known character, the vampiric, gleefully numeric Count Von Count, debuted in 1972. Nelson played over 150 distinct roles in his forty years on Sesame Street — imagine the fun the Count would have with that! The numbers alone testify to his vast versatility. Highlights include the well-meaning Herry Monster (especially singing with Louise Gold); Grover’s exasperated foil Mr. Johnson, a comic straight man worthy of Tony Randall; and the full-body, two-person puppet Snuffleupagus, Big Bird’s imaginary best friend (paired again with Hunt).

Yet the magic of Nelson’s acting lies not just in his nuanced characters, but in his ability to make himself invisible. You could say he sometimes played a supporting role — and sometimes he played all of them! In a number of the early sketches, such as this one, Henson plays one character, Oz a second, and Nelson performs all of the other characters, in unrecognizably different voices. One imagines him throwing down one puppet, picking up another, going in and out of the frame.

This extra dimension of illusion draws many people to puppetry, with the performers not limited to their physical bodies, their embodied identities. And yet this deliberate invisibility sometimes means that puppeteers don’t get recognized for their work — for they have done it almost all too well.

The Muppet Show: Living Large

In 1975, Jim Henson turned to Joan Ganz Cooney, founder of Sesame Street, and said half-jokingly, “Why did you have to be so successful?”

Henson was kidding, presumably, but the remark reflected his concern that the Muppets were being pigeonholed as “kiddie entertainment,” as Christopher Finch puts it, despite countless appearances on shows for adults – The Ed Sullivan Show, The Today Show, even a season on Saturday Night Live. In fact, by 1975 the Muppets had appeared on practically every major show on television – except one of their own.

Help came in the form of Lord Lew Grade, a British media mogul, who offered to fund the show on the condition that Henson use his Elstree Studios, outside London. So the Muppet crew hopped the pond, and The Muppet Show was born.

Nelson was among the show’s five main cast members: Henson, Oz, Nelson, Hunt, and Dave Goelz (best known for Gonzo). Nelson’s versatility on the show was tremendous, from Robin, Kermit’s nephew, a tiny, almost-five-year-old frog; to a sheepish, gargantuan full-body monster Thog, Sesame’s Herry writ large.

Floyd Pepper, a cheerful bassist reluctantly on the clock, reads like a Nelson alter ego. “I always thought of Floyd as a character who had probably been a beatnik first — just like real life — and then he was into jazz and poetry, and then he probably went along with the chase into rock and roll, because he needed a job,” Nelson said. “He drew the line at punk, as I probably did myself. That’s why I can relate to Floyd.”

Though he “drew the line at punk,” Nelson’s first-year digs at the Portobello Hotel in London’s Notting Hill threw him in with punk royalty. “One time the concierge said to Richard [Hunt], ‘I want you to meet some people,’ and it was the Sex Pistols,” said Nelson.

The Portobello Hotel, akin to Manhattan’s legendary Chelsea Hotel, had a roving roster of colorful guests, including Patti Smith and Loudon Wainwright the Third. “The rooms were so tiny,” Nelson said in what sounds like a Muppet Show joke, “If more than one person was in there, one of them had to be on the bed.” Yet their fortunes soon changed – from “God Save the Queen” to, well, the Queen.

The company boarded the QE2 in May 1977 to film the second season of The Muppet Show – and found themselves suddenly on top of the world. England loved the show – and the rest of the globe soon followed. Nelson’s song “Halfway Down the Stairs” climbed the pop charts, peaking at #7. The cast met the Queen of England, after the annual Royal Variety Performance in November 1977.

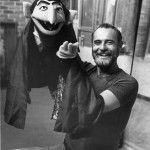

Nelson, Hunt, Dave Goelz, and Louise Gold (in Sweetums costume) meet Queen Elizabeth. Royal Variety Performance, London, November 1977

In 1978, Time magazine called The Muppet Show “the most popular television entertainment now being produced on earth,” viewed by “at least 235 million people in 106 countries” each week, and “applauded each week by more people [around the globe] than there are in the entire U.S.” The show’s guest stars were a Who’s Who of the world’s international celebrities; musically, in particular, Nelson sang with everyone from Pearl Bailey to Bernadette Peters to Alice Cooper.

Nelson moved to a picturesque wood and stucco cottage in the small village of Letchmore Heath, just north of the Elstree studios, and an easy drive from the action in London. “There was always a lot of stuff happening in London, a lot of stuff to do,” Nelson said. Hunt threw legendary parties at his Hampstead Heath apartment, one with cases of Dom Perignon, another with the musicians from Yes.

Nelson and Hunt enjoyed themselves with the same creative zeal they brought to their work. “We had a break from The Muppet Show, and somebody knew somebody at the studio who had a houseboat in Beaulieu sur Mer, in the Cote D’Azur of France,” Nelson said. “So Richard and I took it for a week. We went to a fantastic three-star restaurant in a town back towards Nice, it looked like a big mansion. We had a bottle of wine, and ordered entrees. The entrees were so good, we had another entree each. I think first we had stuffed sea bass, and then we had some steak, probably filet mignon. And another bottle of very expensive wine. It was really expensive, the whole meal. This would have been in the ’70s, and it was like $200 for the two of us. But we were living large in those days.”

But the London years weren’t all parties and adventures. The two were kind friends to each other in the hard times too.

Richard Hunt and Christine Nelson clowning around on the Saturday Night Live set, 1975. Photo courtesy of Jerry Nelson.

During a party thrown by show designer Malcolm Stone, Nelson received word about his daughter. “Christine had a bad episode and started bleeding, internal bleeding in the lungs, while we were at this party,” he said. “So we drove back, and Richard drove me out to my house so I could pack a bag. While I was there I made a reservation on the SST Concorde for that morning. Then we went back to his place and went out in the park and just talked, sat and talked, until it was time to go to the plane.” Hunt was fond of Christine, nicknaming her “Gumbelina”.

The company completed filming The Muppet Show on August 22, 1980, and almost immediately began filming The Great Muppet Caper not two weeks later.

Nelson and Christine have a delightful cameo in Caper, which Henson wrote for them, shot on location in Hyde Park. Nelson flew to America and back to escort Christine to England for her part. “She called it a walk-on,” Gordon writes, “but she had a line and that meant she’d get her union card for the Screen Actors Guild.” Both Nelson and Christine, dissatisfied with what the costume department had provided, wear their own street clothes in the shot.

The company also filmed much of The Dark Crystal in this period, with Nelson later voicing the deliciously repulsive Skeksis emperor, a notable role.

In September 1982, Christine Nelson lost her battle with cystic fibrosis, at the age of 21. “Certainly when you lose a child, life changes,” Nelson said. “Your life changes. I think about her a lot, still. I still love when I can have a dream…. It’s a blessing when you have those dreams, some extra time.”

Nelson put down roots on outer Cape Cod around this time as well, finding the peaceful scenery a balm for his grief. Hunt introduced him to the region, having discovered it himself as a mother’s helper in high school. “I was coming back [from England] and I wanted to rent his house here,” Nelson said in Truro. “It’s funny, because when he was buying that house in ’79, he said, ‘They’re selling these houses, you wanna buy one?’ I said, ‘Richard, I’m not going to buy a house in a place I’ve never been!’ And I didn’t, fool that I am.”

Cape Cod also served as picturesque backdrop to Jerry and Jan Nelson’s beach wedding, on July 16, 1984, with Hunt playing the Master of Ceremonies. Jerry and Jan remained married until Nelson’s death. The couple rented intermittently on the Cape until buying a house in Truro in 1996, just down the road from the ocean.

Fraggle Rock: ‘The Finest Collective Work’

By the mid-1980s, Nelson and Hunt were the “old hands” on Sesame Street, as Henson and Oz were often occupied with other work. “In later years it was really Richard and Jerry who held down the fort,” said Kevin Clash.

A similar independent dynamic existed at Fraggle Rock, the international children’s series that aired from 1983-87. “Busy with other projects, Jim gave the Fraggle Rock team more autonomy than any previous group involved with a major production,” writes Christopher Finch. Nelson agrees: “When we did Fraggle Rock, that was the first thing where Jim wasn’t around all the time. That was the first show that Jim pretty much trusted everybody and knew that everybody would work to his standard.”

Henson had lofty ambitions for Fraggle Rock. “Jim… sat us down in his front room in Hampstead and said our task was to create a series that was going to stop war in the world,” said Fraggle producer Duncan Kenworthy. The show is a valiant shot at this dream, featuring three tribes – Fraggles, Doozers, and Gorgs – whose factionalizing belies their interdependence, much like the residents of our own globe.

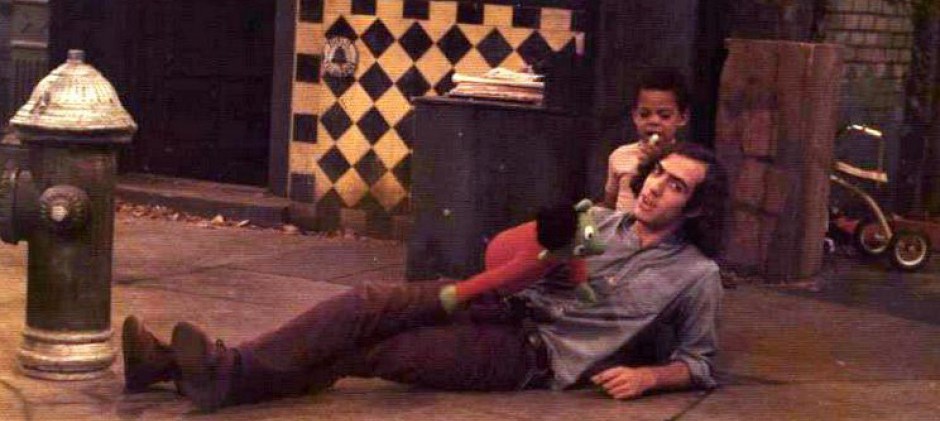

Jerry Nelson performing Gobo Fraggle. Toronto, ON, mid-’80s. Photo courtesy of Warrick Brownlow-Pike

Fraggle Rock takes Nelson’s usual invisible ubiquity to new levels, hiding in plain sight. He plays a major character in each sub-world, sometimes performing more than one character at a time. “If they were doing Trash Heap with Gobo, I would do the Trash Heap, and I would have prerecorded both those lines,” Nelson said. “Either that, or, if it wasn’t very much, I could switch. I could do both.”

He got in some trouble for the trash heap. “I based Marjory on Maria Ouspenskaya, the great Russian actress,” Nelson said. “Somebody wrote an irate letter saying, ‘I’m so disappointed in your show. My son asked me why the trash heap sounded like Grandmother. So you’re equating Jewish grandmothers with trash.’ So for about four or five shows we went outside that. I did an English, I did a black… I said, ‘Okay, we’ll just offend everybody, and then I’ll go back to being the trash heap.’”

In keeping with its international nature, the show was filmed in Toronto. “Henson had this whole history in Toronto, with ‘Hey, Cinderella,’ ‘Musicians of Bremen’ and ‘Emmett Otter’ all shot up here,” said Fraggle producer Lawrence Mirkin, who feels the show and the city were a perfect match: “Given the show’s commitment to interdependence and a global consciousness, I can’t imagine it being filmed anywhere else.”

Fraggle Rock kept an exacting schedule, grinding out an episode per week. “Friday night came; if we weren’t done, we went until we were done,” Nelson said. “I think the latest one they ever had – I finished early for that one, thank goodness – but they worked until 3, 4 o’clock in the morning to get the show done. Often I’d jokingly say, ‘I didn’t want to have a 9 to 5 job so I took an 8 to 8:30 job.’ 8 in the morning until 8:30 at night!”

But the company played as hard as they worked, delighting in each other’s cameraderie even when the cameras were off, especially on what they dubbed “Frosty Friday”. “When we would finish shooting on Friday night… director, writer, cast, production team and crew would all gather for refreshments (Frosty Friday) to discuss that week’s shoot, problems that arose and were dealt with and how we could better resolve those issues if they came up again,” Nelson said with characteristic modesty. Said performer Robert Mills, “Jerry would put it on his tab, and it was always covered.”

Fraggle Rock completed filming on May 15, 1986, with a merry wrap party. “We were all sad to see the end of the show, and most felt it was the finest collective work any of us had done to that date,” Nelson said years later. “I still feel that way.”

In the late 1980s, Nelson also performed in the ABC special The Christmas Toy and a number of characters on the underrated Jim Henson Hour, in addition to his usual steady output on Sesame Street. There was little inkling of the changes that would soon rupture the Muppet world.

A New Era

Dave Goelz, Frank Oz, Kevin Clash, Steve Whitmire, Nelson and Hunt at Henson’s memorial service, NY NY, May 21 1990.

Performers and fans alike were stunned when Jim Henson suddenly died on May 16, 1990, of Group A stretococcal pneumonia, at just 53 years old. “There was just no way to describe his passing other than shocking,” writes Michael Davis.

Over five thousand mourners packed Manhattan’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine for Henson’s May 21 memorial service, in which Nelson, as Floyd Pepper, gave a sweet speech in memory of their “fearless leader,” and with Louise Gold sang a moving version of Emmet Otter’s “When the River Meets the Sea”.

Richard Hunt, serving as Master of Ceremonies, delivered the final eulogy. Though he was speaking of Henson, his words could just as easily apply to Nelson or himself, the presence of spirit all three brought to both work and play, good times and bad. “Jim did not cling to the past,” Hunt told the mourners. “He did not worry about the future – that would work itself out – and he did not live for the moment. Instead, he lived in the moment. Because that’s all we really have.”

Just a year and a half later, on January 7, 1992, Hunt died of HIV complications in Manhattan’s Cabrini hospice. He was just 40 years old.

If Hunt’s life was a sprint, Nelson’s was a marathon – or perhaps a relay race. Many see Nelson as “the rock” of the Muppets in the early ’90s, providing a steady ballast during this time of great transition, as the Muppets adjusted to the losses of Henson and Hunt, as well as Frank Oz’s gradual move away from Muppet projects. “At the center of it all,” Matthew Soberman writes, “Jerry Nelson… played a huge role in ushering in and mentoring a new generation of performers to carry on that legacy.”

As the Muppets underwent a changing of the guard, Nelson found himself the old guard. He saw Sesame Street through its own era of transition, its move to a new studio and changeover in personnel and sensibility. He pulled off a “hat trick” of three major roles in The Muppet Christmas Carol, which Anthony Strand praises as “the brightest spotlight he ever got as a Muppet performer.” And even his tiniest characters came fully to life on the promising Muppets Tonight, a tentative descendant of The Muppet Show.

By this time, puppeteering had become second nature. Nelson spoke to me in Truro of the Zen of puppetry: “What often happens is, the puppet is right, you’re right, the words are right, and it just goes somewhere – it’s not like you’re thinking about it; if you were thinking about it, it wouldn’t happen. It’s very zen, in a way. The target you’re aiming at is yourself.”

In 2001, Nelson began transitioning out of some of his roles, citing health issues. He wrote on a fan forum in August 2006, “I have COPD which is c[h]ronic obstructive pulmonary disease generally and emphysema specifically. I have had this for fifteen years or so but only in the last four years has it become problematic.” In 2004 Nelson was also diagnosed with prostate cancer, treating it successfully with radiation. Yet he continued to perform, doing voices if not always the heavy physical puppeteering.

On the 40th anniversary of Sesame Street in 2009, looking over his long career, Nelson wrote, “It’s funny when I think about it because at least twenty of those years I denied being a puppeteer. I was an actor who was working with puppets until a film or stage job came along and all I really wanted to do was sing.” He had come to appreciate where the work took him, and where he had taken the work.

The following year Nelson released Truro Daydreams, a blithe, folk-blues recording of his original songs. (His wife Jan painted the album cover.) The song “Tides” “shows Jerry’s true spirit,” writes Ryan Dosier. “He recognizes the ebb and flow of the tides, he understands that fate is fate and ‘everything is what it is naturally.’” As his monk character in The Cube had said, “All is all. Is is.”

Nelson made his last major Muppets appearance just months before his death, as the announcer in the 2011 comeback film The Muppets, a familiar and reliable voice as the Muppets attempted to reinvent themselves once again for a new generation.

My Friend, Jerry Nelson

I met Jerry Nelson through writing the biography of his close friend Richard Hunt, a delicate task. From the start he was consistently open, accessible and generous. He gave me invaluable feedback on my interpretation and portrayal of Hunt, always with great respect for my perspective and the project. He developed a sense of me as a writer beyond the biography, taking the time to get to know me and my work. I earned his trust – and he earned mine.

Just two months before he died, I asked Jerry if he wanted to read over sections of the book. But, I asked, what would we do if we disagreed? I wanted to discuss that before we found ourselves there, because peace was my priority. But Jerry was matter-of-fact: “I know this is a labor of love for you and don’t worry about conflict and resolution.” The words felt like a blessing, like he knew my heart was in the right place. He believed in the book, telling Ryan Dosier, “You’ll have to read about anything more in Max Stein’s book about Richard when it comes out.” As my mother would say, from your lips to God’s ears.

And yet we became friends partly by taking time to not talk about the Muppets. On a long weekend on the Cape in June 2011, I found that we had plenty else to talk about – a love of music from Lena Horne to Led Zeppelin, a devotion to the natural world, an eye for birds, a love/hate relationship with New York. Nelson could also be quietly companionable, especially out in nature, a rare trait – just being present and appreciating the moment.

One afternoon found us drinking homemade absinthe at his friends’ art gallery, the group clustered around an elaborate steampunk-looking contraption through which the absinthe dripped very slowly into a tiny glass. I didn’t like the bitter drink, so after a while Jerry drank mine. He said he hated to see it go to waste.

Generosity was a kind of game for Nelson and Hunt, another fun competition, so I was smug to snatch up the check at brunch one afternoon in Provincetown. Only later did I realize Nelson had left the check idling at his elbow for ages, teaching me to take my turn in the generosity game. I was excited to “win” a round, even if he had let me win.

Finally, Jerry Nelson was truly cool, old-school, Johnny Cash, Nobody-Puts-Baby-in-the-Corner cool. “Never be nervous about anything if you can help it,” he wrote me, when I was worried about something or other. He projected a calm confidence that was never arrogance, but simply a rooted steadiness. And a mirth beneath the surface, too, a sense of mischief, of getting away with this great life.

In January 2012 Jerry started posting haiku. There seemed a certain rightness in that – the Count counting syllables. I wrote a haiku for Nelson, another game.

The Count Writes a Haiku

Five! Five syllables!

Seven! Seven syllables!

Five more! Ah ah ah!

Jerry loved the haiku: “I know the Count and I approve this message! Max Stein, that is so spot on beautiful. I wish I’d said that.”

In a sense, though, Nelson did say that – by animating the character of the Count so vividly, by bringing such delight to a subject as seemingly mundane as numbers. “Really, all of these characters are just elements of ourselves,” Nelson said. “I think there tends to be a part of us in everything, and we see that, and then we expand that, blow it out bigger than it actually exists in us.” As long as The Count has something to count (to numerate, to notice), he’s happy. The Count, like Nelson, is mindfulness in action – punctuated, of course, with a laugh.

On August 23, 2012, Jerry Nelson passed away peacefully in his home on the Cape. I called Mallory to reminisce about when we’d first met him. I told her what Nelson had said when I asked him about losing Christine, when I apologized for bringing up a sad memory.

“It doesn’t hurt us to be sad sometimes,” he had said. “I believe it teaches you compassion. And maybe a little humility. So, sad’s not too bad, unless it’s about something really bad. Those kinds of sad, people dying, it’s just part of what life is.”

And then Mallory told me all about her new baby daughter Daria, thriving and cherubic, born just five days before Nelson’s death. Just part of what life is… The happy and sad seemed all bound up together. I felt somehow like Nelson would understand.

Sources

Blaylock, Cheryl. Personal interview. NY, NY. October 12, 2012.

Christie, Ed. Personal interview. Cape Cod, MA. June 15, 2011.

Davis, Michael. Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street. New York: Penguin Books, 2009.

Dosier, Ryan. “Interview with Legendary Muppeteer Jerry Nelson”. The Muppet Mindset. November 12, 2010. <themuppetmindset.blogspot.com/2010/11/interview-with-legendary-muppeteer.html>.

________. “Jim Henson’s 75th Birthday: The Effect on the World”. The Muppet Mindset. September 27, 2011. <themuppetmindset.blogspot.com/2011/09/jim-hensons-75th-birthday-effect-on.html>.

________. “Truro Daydreams: Jerry Nelson’s Best”. The Muppet Mindset. <themuppetmindset.blogspot.com/2012/08/truro-daydreams-jerry-nelsons-best.html>.

Finch, Christopher. Jim Henson: The Works: The Art, the Magic, the Imagination. New York: Random House, 1993.

Freudberg, Judy. Personal interview. NY, NY. August 17, 2010.

Gordon, Jackie. Give Me One Wish. New York: Berkley Books, 1988.

Hennes, Joe. “A Chat with Jerry Nelson”. Tough Pigs. December 8, 2009. <toughpigs.com/a-chat-with-jerry-nelson-part-1/>.

The Jim Henson Company. “Jim Henson’s Red Book”. “12/1-5/1965 – ‘Tape 2 Dean shows in Hollywood with Jerry Nelson’”. <henson.com/jimsredbook/2011/12/03/121-51965/>.

________. “3/30/1976 – ‘VTR Goro Special then Kyoto.’” <henson.com/jimsredbook/2012/03/30/3301976/>.

________. “9/4/1980 – ‘Begin shooting The Great Muppet Caper! Begin in Battersea Park – bicycle sequence – Brian operates Marionettes.’”. <henson.com/jimsredbook/2011/09/04/941980/>.

________. “5/15/1986 – Fraggle Rock ends in Toronto.” <henson.com/jimsredbook/2011/05/15/5151986/>.

Mills, Robert. Personal interview. Toronto, ON. July 6, 2010.

Mirkin, Lawrence. Personal interview. Toronto, ON. July 6, 2010.

Muppet Wiki. “Jerry Nelson”. <muppet.wikia.com/wiki/Jerry_Nelson>.

________. “Floyd Pepper”. <muppet.wikia.com/wiki/Floyd_Pepper>

Nelson, Jerry. Personal interview. Truro, MA. February 13, 2010.

Nelson, Jerry. Response to “How is Jerry Nelson doing?” thread on Muppet Central Forums. Muppet Central. <muppetcentral.com/forum/threads/how-is-jerry-nelson-doing.2198/#post-44700>.

Plume, Kenneth. “Still Counting: An Interview with Muppeteer Jerry Nelson”. March 1, 1999. <muppetcentral.com/articles/interviews/nelson1.shtml>.

“Richard Hunt; Puppeteer, 40”. New York Times obituary. January 09, 1992.

Robertson, Nan. “Bil Baird, Creator of Puppets, Is Dead”. New York Times obituary. March 20, 1987.

Skow, John. “Show Business: Those Marvelous Muppets”. Time magazine. December 25, 1978.

Soberman, Matthew. “Jerry Nelson: The Rock of the Muppets”. Tough Pigs. September 2, 2012. <toughpigs.com/jerry-rock/>.

Strand, Anthony. “It’s In the Giving of a Gift to Another…” Tough Pigs. September 1, 2012. <toughpigs.com/jerry-xmas/>.

Swanson, Steve. “The Muppetcast”. Show #41. Audio podcast. January 20, 2008. <muppetcast/WordPress/show-41-january-20-2008/>.

Thank you so much for your work! Can’t wait for the book! ✌️❤️

a great piece of memory for someone so talented .He is honored by people who admire and appreciate nd value their work …..I have been trying to find out about Don Hinkley I hope someone can shed some memories of a talent seem forgotten

Beautiful! 🙂

I aged out of their saga before The Count and the show. You’ve brought me Jerry Nelson and the Muppets in an elegant package. Thanks, Max.