Writing Richard Hunt’s story often unexpectedly yields its own good stories. In summer 2014, I was on Cape Cod interviewing Hunt’s sister Kate when she mentioned their “phenomenal” high school music teacher: Gail Poch. At Northern Valley High School in suburban New Jersey, Poch conducted Hunt in multiple choruses, directed him in school musicals, and hung out with him and his friends as they crowded into Poch’s room during free periods, playing records and rehearsing lines and singing, always singing. Poch wasn’t much older than the students, a beatnik who laughed at their jokes as he smoked endless cigarettes and swigged from a seemingly bottomless thermos of coffee. “I wonder how he is,” Kate said wistfully.

I looked him up the next day, still on the Cape. I figured I’d find an obituary – but instead I found Poch! He lived in the Boston area, where I was already planning to stop on my way home. I dialed him right up. “I’m sorry to bother you, but is this Gail Poch, the music teacher?” It was. “I’m writing Richard Hunt’s biography, and I was wondering if you might be able to meet for an interview…”

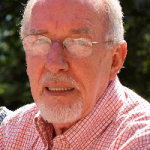

I met him just a few days later, at a restaurant in Concord. I could see immediately what made him a good teacher. He had a certain quality of attention, of open-minded, nonjudgmental listening. He seemed truly curious about what you had to say, whatever it might turn out to be, and had a way of reflecting your words back to you so you heard more in them, or the potential for more. We talked not just about Richard Hunt, but about our shared field of teaching, how to bring out the best in students. After we ate, we drove out to Walden Pond; ever the professor, he said an English teacher couldn’t visit Concord without seeing where Thoreau had lived.

In 1961 Poch was fresh out of college, with only a year of teaching in south Jersey under his belt, when the Northern Valley band director called him to suggest coming in for an interview. Poch drove up in his “old, beat-up, 1954 Volkswagen Bug, not sure if I would make it to New Jersey.” But the car held out, and so did his luck; he landed the job.

Four years later, Richard Hunt was a freshman amidst a crop of “outstanding” students. “That group of personalities instilled inventiveness and creativity, and it really blossomed,” Poch said. These students used Poch’s classroom as a refuge from the more conservative elements at Northern Valley. Assistant principal Anthony Colantoni, a “strict disciplinarian,” enforced the dress code – skirts for girls, nice slacks for guys – and even called Poch into his office one day for wearing a cardigan sweater, rather than a suit jacket, with a nice shirt and tie: “You don’t wear a sweater. You wear a coat.”

Yet for all his unorthodoxy, Poch brought out the best in his students. Hunt “burst onto the scene” in his freshman year musical, Cole Porter’s Broadway hit Kiss Me Kate. “Even in that first show, whenever he was onstage, you knew the audience was going to be on their toes,” says Poch. “It didn’t take him long to figure out who on stage they should be watching.”

But as a chorus teacher, Poch developed Hunt’s instinct for collaboration, rather than competition. “I wanted them all to learn to sing,” says Poch. “I was not one that prompted talented singers to be the star. If there were soloists, I’d rotate, so everyone had a chance.” As Hunt gained confidence in his abilities, he generously shared his talents. “When I was first trying to figure out how to sing harmony, he would jump in and help me, even though he didn’t know me that well,” says friend Terry Minogue. Hunt had little concern about strengthening a potential rival; if a fellow performer improved, then so did the performance as a whole, his ultimate aim.

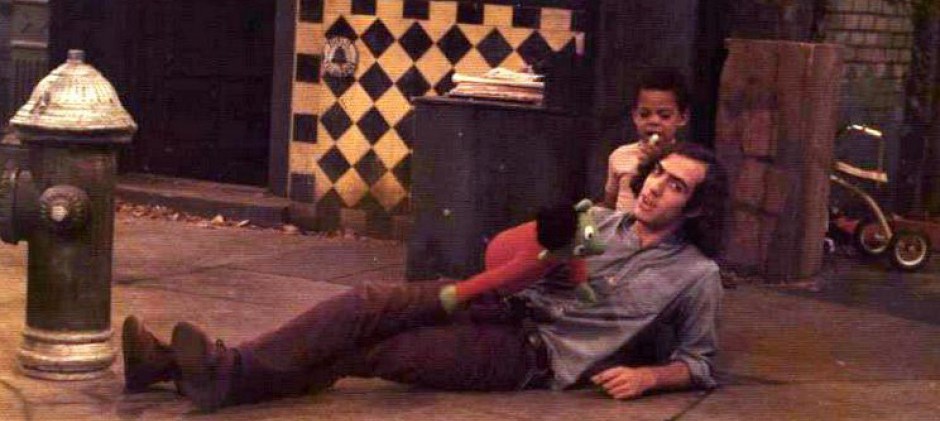

So Hunt was elatedly in his element when Poch brought in a Broadway choreographer to work on the musical his sophomore year, The Pajama Game. Gerald “Buddy” Teijelo had been the dance captain for Broadway shows 100 in the Shade and Subways Are for Sleeping; he and Poch had hit it off during a season of summerstock. Teijelo’s talents and reputation created a Glee-like atmosphere at Northern Valley. “All the guys in school got interested in trying to be dancers, including football players and basketball players, and the coaches and administration went along with it,” says Poch. “So we ended up with athletic dancers who could really move, and if they couldn’t move he taught them how, and did choreography like you don’t see in high school shows. That put the show on a whole new level, even though it was done in a gym.” Hunt played Vernon Hines, the smooth-singing, knife-throwing second male lead, dancing a soft shoe with his sister Kate that “brought down the house.”

But Hunt’s junior year musical, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, really took the cake. Students danced Broadway-caliber choreography with the return of Buddy Teijelo, and wore costumes from the recently-shuttered Broadway run, miraculously wangled by Poch, who reports proudly: “I don’t mind saying it was the best show we had ever done.”

Poch had chosen Succeed with Hunt specifically in mind: “I wanted to pick a show that he could do the lead in, and I pictured him as J. Pierrepont Finch,” the everyman, rags-to-riches main character. Yet Hunt as usual landed the second male lead, the scheming antagonist Bud Frump. But he knew well how to command the audience’s attention. “If he couldn’t get the lead, he made the side the lead,” says friend Geni Sackson. “He made it hysterical.” One night a lackluster number – set in a men’s washroom – was losing its audience. “Richard, to make up for that, was doing some very funny things,” recalls Minogue. “He turned around and pretended to use the urinal on the back wall. He did shaving, he was doing his armpits, he was plucking his eyebrows – whatever it took to get a laugh.” Yet Hunt minded the accusation that he was trying to upstage the scene’s main actor. “He would say, ‘I wasn’t trying to upstage him, the scene just wasn’t working.’” Despite his playful attitude, Hunt took performing very seriously. “Other kids may have been doing the school show; he had a vision for himself,” says Sackson. “He was making a career.”

Poch left Northern Valley before Hunt’s senior year – “Much to my chagrin. I had very mixed emotions about leaving, because I wanted to see what he would do.” But the two stayed in touch while Poch taught at Temple University in Philadelphia. “Richard became almost like a foster son,” Poch says. “He made a contact with our family like no other student I ever had. My wife just loved him. He didn’t come down that often, but when he did, it was like we’d just seen him last week.” In one of Hunt’s last visits, he narrated an Arthur Honegger oration with Poch and a group of students. Poch retired from Temple in 2000.

After our interview, Poch and I kept in touch over email. This spring, I finally sent him a draft of the high school section; he’d been eager to see it. In mid-August, I heard back from his son Eric: Poch was in ill health, but Eric had printed out the pages to bring to him. That was the last I heard. Just the other day, I looked him up again – and this time, I did find the obituary. He had died soon after his son’s email. I wonder if he ever did see those pages, and what he thought.

For those keeping score, we have lost 4 of the 80 people I have interviewed for this book, and another has lost her memory. I am doing this project just in time.

Obituary here. Rest in power and peace.