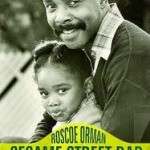

You probably know Roscoe Orman best as Sesame Street’s Gordon Robinson, the iconic role he’s played since 1974. Yet Orman’s fame as Gordon masks his artistry and experience as a multifaceted character actor, performing everyone from lawless pimps to Lincoln Perry (the controversial creator of Stepin Fetchit), everywhere from Harlem’s historic New Lafayette Theater to Broadway to the big screen.

You probably know Roscoe Orman best as Sesame Street’s Gordon Robinson, the iconic role he’s played since 1974. Yet Orman’s fame as Gordon masks his artistry and experience as a multifaceted character actor, performing everyone from lawless pimps to Lincoln Perry (the controversial creator of Stepin Fetchit), everywhere from Harlem’s historic New Lafayette Theater to Broadway to the big screen.

“People think what they see on TV is real,” Orman says of being mistaken for Gordon. Read our recent interview to discover the man behind the icon, including his thoughts on Richard Hunt’s “life mission,” trying his “hand” at puppetry and why Whoopi Goldberg is a “human Muppet”.

Jessica Max Stein: What are some of your memories of Richard Hunt?

Roscoe Orman: He never failed to make someone laugh. That seemed to be a large part of his life’s mission, to make people laugh. You never knew what would come out of his mouth. But whatever it was, it always would get a response.

I had a few memorable moments on the set with him. I was doing a bit with Forgetful Jones, who’s one of my favorite characters. He was just brilliant in that role. Whatever was in the script, you could just throw it out the window, because you knew he was going to come up with stuff that no one could have written.

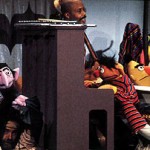

Forgetful Jones, Orman, Orman’s real-life son Miles, and Loretta Long. Sesame Street set, late 1980s.

As usual, Forgetful would always forget the person’s name. He would always call you something else. He really caught me off guard one day when he started by saying [Forgetful voice]: “Yeah, Roscoe!” And everyone in the studio cracked up.

JMS: Speaking of Forgetful Jones, another Sesame performer told me a story about you and Forgetful, with Hunt making a suggestive joke. She said, “Gordon gets paint on his nose, which he’s supposed to wipe off with a rag. Forgetful Jones is saying, ‘Well, you’ve got paint on your nose.’ Gordon wipes it off and he goes, ‘Is that better?’ ‘No, your face is still covered in paint! You’re scarred for life!’” What is it about Richard that he gets away with that joke?

RO: Richard’s personality, spirit, temperament, character, was so open and clear and without any sense of bias or anything like that, that for him to do that, it’s just funny. I could imagine, without a lot of effort, someone else trying to do that, and it falling flat, like, “Oh my God, did he say that?” But Richard could say almost anything, and it would be funny. He didn’t have a mean bone in his body. Not one. He was just the most loving, kind spirit you can imagine.

Combined with that was his incredible delivery of a punchline. He’s someone who could probably read the encyclopedia and make it funny. It was almost like he was making it up at that moment, it wasn’t something he had already thought of. It was in the moment.

JMS: He was great in terms of spontaneity.

RO: There was a lot of that when Richard and Jerry [Nelson] were doing partners: the Two-Headed Monster and Biff and Sully, who were, in my opinion, the best comedy team I’ve ever worked with. And the fact that one of them was silent just made it unique.

JMS: When people ask me if he “did the voices”, I often tell them to watch Sully. I say, “Look, there’s no voice, and you’re laughing. Notice how physical it is.”

RO: Right. And part of it is the design of the puppet, so the character is already there. But his responses to everything that Biff would say was hilarious! That’s the kind of thing you can’t teach someone how to do. It’s a gift. It’s an intuitive kind of thing, which I’m sure Richard and Jerry worked on, but it sprang out of their chemistry, because they were both amazing performers. And together they were even better.

JMS: Jerry was a wonderful person, period.

RO: Oh yeah. I’d probably say that, as a personal friend among the Muppets, he was the one I felt closest to. He and I shared so many similar tastes. He was just a very cool guy.

And Jim [Henson] was this very gentle Zen master, always guiding everything. With a whisper. Sometimes you could hardly hear him making these suggestions, in his very polite way. “Could you just try it maybe like this?” I’ve never been around anyone who had such a gentle way of changing everything. He was the creative genius behind the Muppets, and he knew the capabilities and limitations of every one of those characters and performers. Back in those days, it really was an ensemble.

JMS: That’s what everybody says. So collaborative.

RO: Oh my goodness. We would come in before the season, and have meetings about our characters’ lives. What’s Gordon going through these days? What should we see from Gordon? It was so cool, to have that kind of collaboration. It was amazing. I think we all regretted seeing those days end, but we appreciated the fact that we had them.

That’s something that could not have continued without the leaders, without Jon [Stone] and Jim and Dulcy Singer, who was also very much a part of that, creating the environment of that early chemistry.

JMS: I think a lot of different factors went into that change. You had the changing of the leadership in that sense, then you also had that change in children’s television in the early 90s.

RO: Yes, absolutely.

JMS: And also, it’s tricky, because, what if it had stayed the same? I don’t know if you could do the same thing for 40 years, if that energy would have just gone out of it anyway.

RO: No, you’re absolutely right. I’ve been a part of other creative teams that have lasted for periods of time, maybe a year, two years, five years. You reach a point where the excitement of the coming together, just bursting with enthusiasm and creativity, that can’t last forever. It begins, it peaks and then it begins to wane. So obviously that would have been the case, that was the case, with Sesame Street as well.

But we just did an incredible thing on incarceration on Rikers Island last week, that and military families, just a wide range of really proactive, wonderful efforts to reach out and support communities and parents and children. That’s the kind of thing that I think the workshop has learned how to do, in terms of approaching certain issues that are really difficult.

Of course the first big one we did was Mr. Hooper [when actor Will Lee died]. Which was huge! It was a great show, and it was the right choice of what to do. The other choices would have been to recast the role with another actor, or just develop a storyline that Mr. Hooper moved away. But they chose a very courageous path with that: Let’s acknowledge the fact that Mr. Hooper has died. I thought Norman [Stiles]’s script was brilliant. It was definitely not a story which any of us had to try to act. Because we were actually in that grieving state, still.

JMS: Will Lee, that’s a wonderful story. How he was able to come back from being blacklisted to be on Sesame Street.

RO: Oh yeah. He was one of my heroes, and closest friends. I just spent as much time with him as I could. I knew that every moment I had with him was a gem. He would come to see all of my work outside of Sesame Street. He was a wonderful acting teacher. He had some very famous students, like James Earl Jones and others. He was their mentor, and I was among his mentees. He would come and we’d always have a meal after the show, and he’d always tell me what I did right, and what I did wrong. [laughs]

JMS: Many puppeteers describe themselves as actors, and puppeteering as another form of acting. As an actor, what do you think?

RO: Well, one thing I’m sure of is that good puppeteers can be much better at acting than good actors can be at puppeteering. Without a doubt. Puppeteering requires a skill in addition to acting.

I know there are some actors who resent the idea that puppeteers are considered actors. I think that’s ridiculous. I really do. Just because we actors who are not puppeteers are into ourselves, who are our instruments, of course we can get a limitless number of nuances from your own self, because we human beings have so many more capabilities than a fabricated puppet. But the fact that great puppeteers can simulate, come close to, this human sensibility is just phenomenal.

I admire anyone who even tries to be a puppeteer, not to mention the ones who are really good at it. I’ve never seriously tried on any puppets – I’ve put them on my hand – but the best experience I’ve had on camera, to give me a sense of this heightened respect, is I did an “Elmo’s World” where the topic of the day was hands. I don’t think I had a puppet on my hand, I think it was just my hand, Gordon’s hand. But first of all, the physical…

JMS: Just holding your hand up there.

RO: That was enough right there to say, “Well, that’s it. I could never do this.” Eventually, about halfway through the taping of the segment, Matt Vogel had to come in and hold my arm up. Because there was no other way I was going to get through it! To hold your hand up that long, and manipulate, even without having the puppet! And then to do the scene, because I’m talking as a hand, wow! I had no idea how difficult just that part of it is. But at the same time, to do a character, and make it distinguishable.

It was very informative to me to stand and watch the segment between Robert DeNiro and Elmo, when DeNiro was on the show around ten years ago. Obviously DeNiro is considered to be one of the greatest film actors, ever. I’m a huge fan, I think he’s one of the best, but he was completely disarmed and disoriented in working with Elmo. He wasn’t really interacting with the puppet.

I contrast that with certain performers, like Robin Williams, Whoopi Goldberg, Billy Crystal. They’re like Muppets themselves. They are human Muppets. So they get it right away. You put them in a scene with a Muppet, they’re equals.

It took me probably one season of primarily looking at the kids, my first year on the show. It’s something you have to learn how to do.

JMS: Do you have any thoughts on this year’s Tony’s? In your book, Sesame Street Dad, you talk about the opportunities for black actors on Broadway in the late 80s, and how it’s never really been repeated, but this year it seems like things might have changed.

JMS: Do you have any thoughts on this year’s Tony’s? In your book, Sesame Street Dad, you talk about the opportunities for black actors on Broadway in the late 80s, and how it’s never really been repeated, but this year it seems like things might have changed.

RO: Oh yeah, I think this was a really good year, for African-American performers in particular. I’m hoping I can arrange to get some tickets for Trip to Bountiful, I want to see Cicely [Tyson]’s work. But there are many film actors who are not really good stage actors. There’s a different craft involved. You’ve got to project, and you’ve got to have a certain presence. Stagecraft, knowing how to move. So I’m really intrigued about her performance.

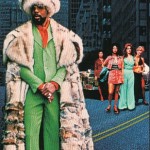

The first film I ever did, Willie Dynamite, fortunately I had a large role so I had time to develop an understanding of how you had to just tone down everything. It was kind of a large character anyway, so I could play him large, but by the end of the filming, I think I had really begun to understand the differences between film and theater acting.

I really admire great film actors. But it’s different. And there are only a few lead actors who continually make that transition back and forth. Like Dustin Hoffman, Denzel Washington, and Al Pacino. But there are people like DeNiro and others, he went back, he did a small production of something twenty years ago, and said, “Okay, that’s it, I’m not going to do theater anymore.” But he had really perfected that minimalist style of film acting.

Acting and preparing for the stage requires a different kind of commitment, in terms of memorizing a whole play, as opposed to, you get a page every day or two on the set of a movie, and you don’t have to stick exactly to those words. Good directors don’t exactly want you to.

JMS: There’s something so special about theater. You’re all in this theater together. You’re all in this moment together. Even if the audience is just watching, there’s something much more shared about it, something much more alive about it.

RO: My favorite kind of theater is where the fourth wall is broken, and the audience is a part of the play. Probably the most fun I’ve had in that vein is the one-man play, The Confessions of Stepin Fetchit.

JMS: Matt Robinson, who wrote Confessions, preceded you as Gordon on Sesame Street, and also wrote for The Cosby Show. His work seems underappreciated.

RO: Yeah. Matt was a very special guy. I first met him, briefly, long before Sesame Street. My first TV job was in Philadelphia, his hometown, where he had started his career at WCAU, the CBS affiliate as a writer, producer, director. I did a few shows for them.

And then, at the tail end of my New Lafayette Theater days in Harlem, a couple of my associates there were very close friends with Matt. As a matter of fact, one of these friends, Stan Lathan, was the one who suggested I try out for Sesame Street. He was directing segments at that time. And at that point Matt was still writing for the show, as well. He had stepped down from the performing.

JMS: He was a good Gordon.

RO: Yeah. In the minds of all the kids, he was Gordon. Which I soon found out. It took me a year for them to accept me as Gordon.

JMS: That must have been a challenge.

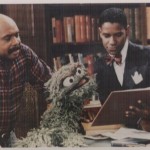

RO: It was. So he and I remained close. We collaborated. He was writing segments for a character named Roosevelt Franklin, and I was one of the supporting characters, I was Hard-Head Henry Harris. [laughs] We had so much fun doing those. We did maybe just a few seasons of that, and it was gone.

JMS: Someone once said to me, “Characters die off when the mail comes in.” But I loved Roosevelt Franklin. I’m sorry he was controversial.

RO: Yeah, well, the politically correct era emerged, and there were certain things we just couldn’t do without people saying, “That’s not really appropriate.”

But he [Robinson] was a really brilliant guy. That play was a great, generous gift that he gave me. I toured it around the country, took it to various venues. I loved doing that. I thought it was a great biographical tribute.

Lincoln Perry [who played Stepin Fetchit] lived in an era that very few of us can imagine. He was older than my grandfather. The times that he was working in, there were no featured black actors in film at all. Not one. So for him to take what was basically no real opportunity at all, and turn it into a career! He made over a million dollars, which in those days was like a billion. He had an amazing personality off-camera, larger than life. Very complex person behind that character.

And that character came from a history of prototypes that had been a part of the African-American experience, very legitimately so, and he brought it onto the screen. Most black audiences understood. Working class black audiences, they found him hilarious. They were in on the joke, you know? But there were others who thought it was demeaning, “We want to move beyond that.” Like the politically correct. You’re not supposed to even talk about that anymore.

JMS: That play is a great example of your work outside of Sesame Street. I imagine that playing Gordon is a mixed bag in some ways. The role is iconic on the one hand, but then it’s often unrecognized that you’re a character actor, who can play a lot of different roles.

RO: Yeah. Being Gordon, if I didn’t have another venue or outlet where I’m acting character roles – theater acting, and film and TV occasionally – I wouldn’t be considered an actor by most people. Most of the other performers, too, have continued to work outside of Sesame Street, but if we didn’t I don’t think that we’d be considered actors. At all.

Orman with First Lady Michelle Obama and Muppet Abby Cadabby at the White House Easter Egg Hunt, 2010.

JMS: I was struck by what you said in your book, that none of the actors on Sesame Street have been nominated for an Emmy, when the show wins an Emmy every year.

RO: Every year. Yeah, I used to talk more about it, but I don’t think about it a whole lot anymore. As long as I can keep doing my theater work. I keep thinking that this next play will be the big [one], something that will really be recognized. I’ve done Broadway, I’ve done a lot of Off-Broadway, regional theater. Very respectable.

JMS: It’s interesting to me, I also find this in writing about Richard, with this kind of acting, when you’re really good at it and you make it look effortless…

RO: It doesn’t look like you’re acting.

JMS: Exactly! It doesn’t. That’s what I had to say to a friend the other day. “He’s not Gordon, honey.”

RO [laughs]: That’s a hard thing to explain, or to get the average audience to understand. Unless they’re in the business or they understand that career, the image of a television show and characters, that life. That’s why we’re in the so-called reality TV show era, because people think what they see on TV is real. It’s always scripted, and yet somehow audiences, the average person who watches a lot of television, they don’t make the distinction. It’s kind of a sad comment on our culture that that’s where we are.

JMS: Do you have anything you’re working on that you’d like to talk about?

RO: I’ve got a few projects. One of which is connected to Sesame Street. I’ve been trying to get the rights to the old vintage songs from the show that have never been recorded outside of the original broadcast, but were really good songs, and do a CD. The musical director, Paul Rudolph, and I are working on that.

Another thing I’m involved in, I have a partnership with a childhood friend who is a great documentarian filmmaker, Ken Browne. We have a company that’s in the early stages of doing a film on the history of African-American jockeys.

The first several championship jockeys in the Kentucky Derby were African-Americans. They were slaves that were recruited to ride these horses, because it was discovered that many of them had a natural ability to ride, which it turns out stems from an African tradition of horse racing which preceded slavery. In the beginning of the Jim Crow era, after Reconstruction, the banning of blacks from anything, those jockeys lost their line of work.

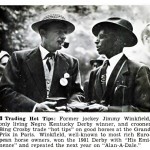

I discovered the story of one of them while hosting and narrating an ESPN special about six years ago called Images in Black and White. A variety of stories of black athletes who were very little known, but were groundbreaking and very important. And one of them was this jockey, Jimmy Winkfield, who won three or four Kentucky Derbys in a row, late 1800s, early 1900s, until Jim Crow banned him from the sport.

So in order to continue his passion, he fled to Russia, and became part of the aristocracy. And then the Bolshevik revolution happened, and he had to escape Russia. He escaped Russia on foot, and wound up in France, where he became the number one jockey in France. He finished his career there, and eventually was invited back to the United States to be recognized for what he was, which was one of the best jockeys ever.

When I read that, I said, “Wow.” So we’re in the process of developing that.

And acting-wise, I’m involved in a play about the rise of a black politician in California who’s trying to become the first governor of that state. We’ve done a few readings of it, and we’re taking it to a festival next month. A powerful political and family drama. Some really good romantic fireworks going on between the politician, his wife, and his former mistress. So a lot of good juicy stuff.

JMS: Thank you so much for doing this interview.

RO: Oh, it was a pleasure. Thank you for doing this, too. I’m really happy that this book is happening. Especially for those of us who knew Richard, it’s really so cool. If there’s any Muppeteer who deserves a book, it’s him.

What a great interview with a very talented gentleman! Roscoe’s character Gordan always gave me a sense of calmness and security when watching, as an adult watching SS with my daughters. To me he is a pillar in the world of child educational television and deserves so much credit for an absolutely magical career. Great interview!