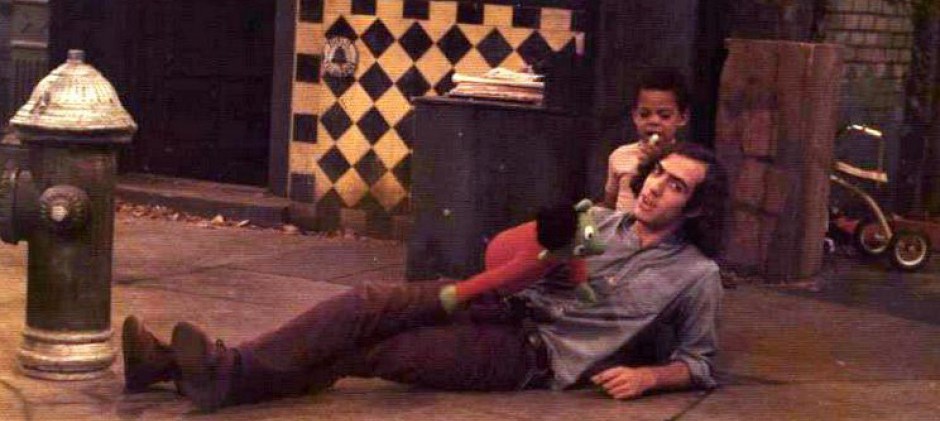

The Mean Genie is one of Richard’s one-time Fraggle Rock characters (episode 309). When sweet, indecisive Wembley Fraggle (Steve Whitmire) lets the genie out of his bottle, the genie immediately takes advantage, testing the limits of his temporary escape, teasing, stealing, lying and committing other egregious breaches of community conduct.

The Mean Genie is one of Richard’s one-time Fraggle Rock characters (episode 309). When sweet, indecisive Wembley Fraggle (Steve Whitmire) lets the genie out of his bottle, the genie immediately takes advantage, testing the limits of his temporary escape, teasing, stealing, lying and committing other egregious breaches of community conduct.

I actually think the Mean Genie is less mean than he seems. He’s been shut up in that tiny bottle all his life (“So small, I didn’t even have enough room to change my mind!”), with no freedom, no autonomy, no choices. Little surprise that when finally released from the bottle, he pushes at the boundaries. He is a genie, a magical creature, with different powers than the rest of us. He can move through walls.

The Mean Genie’s power reaches its apex when he hypnotizes all the Fraggles but Wembley – a spell-binding scene for the viewers as well as the Fraggles – and leads them in singing “Do You Want It,” an anti-authoritarian anthem right up there with Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out.” This is the Mean Genie’s rock star moment, high up on stage, his gold hoop earrings and chains glinting in the dramatic manic lights.

I fell asleep and I started to dream,

Dreamed I was trapped in a nightmare machine,

Everyone giving me good advice,

Everyone saying be neat and be nice.

They want you to leap through the hoops and the rules.

They want to creep through the groups and the schools.

Everyone there in the same old show.

Everyone scared to say “No”.

The Fraggles become both audience and participant, the chorus a kind of call-and-response.

Well, do you want it?

No! Get out of our way!

Well, do you need it?

No! Just take it away!

Well, do you want it?

No! Gonna live for today!

Well, do you need it?

No! Get out of our way!

Then I woke up and I started to see,

Everyone yells when you try to get free.

Nobody cares if you laugh or cry.

Nobody cares if you live or you die.

Ironically, the Genie’s cry for individualism comes at the expense of the Fraggles, who by this point in the song resemble a veritable army, standing in rows, wearing identical brown uniform-type tunics and hard hats. Their dancing is a sort of soldiers’ march.

People got rules for the night.

That’s right!

People got rules for the day.

Hey!

Time to get angry and fight.

Start a fight!

Time to get angry and say,

Well, do you want it?

No! Get out of our way!

Well, do you need it?

No! Just take it away!

Well, do you want it?

No! Gonna live for today!

Well, do you need it?

No! Get out of our way!

But when the genie knocks down a Doozer tower, Wembley, horrified and beside himself, finally exclaims, “Stop! This has gone far enough… I let you out of that bottle and I wish you’d stop all this!” And the genie – being a genie – has to grant the wish.

Wembley manages to emblematize the message of the song, yet in a healthy way that considers both the individual and the community. “I wish I could make you understand the difference between standing up for yourself and just doing what you want to do,” he says – and because it is a wish, the genie suddenly does understand, becoming instantly penitent, volunteering to go back in the bottle.

But Wembley uses his final wish to grant the genie his freedom. What strikes me here is how the genie is genuinely surprised. “You wish that for me?” He seems truly relieved and gladdened. “Your command is my wish!” Finally, after eons of granting everyone else’s wishes, someone has granted his own.

I think we see a little of Richard in the genie, in his playful pushing at the boundaries. This same spirit is what led him to cold-call the Muppets from a pay phone at only 19, to ask if they could use his puppeteering skills. It was a wild, brave thing to do – may we all learn from his example to believe in ourselves.

I see this spirit too in how he “lived for today” – in the stories people tell of his perpetual lateness, how he would streak into the theater minutes before the curtain, how he would read the newspaper until seconds before a performance, put down the newspaper as the camera went on. I see it in his love of fine dining and wine, his deep appreciation for beautiful places like the outer edge of Cape Cod and London’s Vale of Health and the canals of Venice, his great generosity to his family and friends and lovers.

This spirit also made him a brilliant performer, unafraid to ad-lib, to upstage, to push the envelope, to go for the laugh. He was an artist. He was an entertainer. And he created many characters, like the Mean Genie who is perhaps not so mean, that are immortally entertaining – and realistic, and complex.

I have faith in the genie. Now that he’s free, I think he’s going to clean up his act. But I do hope he never forgets to have a good time.

I had the privilege of visiting where Richard Hunt lived in the Vale of Health London on 24th March as well as visiting where Jim Henson lived. It was a very special moment for me, as I have been a massive Muppets fan since the age of five in 1976.

After reading your biography about Richard, I got to discover some of the other characters that he created, one of them was The Mean Genie which I thoroughly enjoyed, he was fantastic at being the villain. What I loved about the episode was the fact was the genie was set free in the end.